We present for you yet another edition of...

Time for another installment of Craig's ongoing

palaeo-art (

mis?)adventure...

Flukes go on Whales... NOT in your Art!

Part:3

Previously on Flukes (imagine catchy suspense music, just like an awesome cliffhanger multi part TV show)

`

Part 1- I decided to try and create some palaeo-art for New Zealand Palaeontologist Ewan Fordyce. This was unrequested art, and this is probably a good thing considering what I first produced! Find out the HUGE mistake I made and the first lesson you should learn from my folly.

`

Part 2- After regrouping from my first embarrassing version of the Shark Toothed Dolphin, I proceeded to try and rework it. However with this second attempt my strengths and preferences from usually creating Dinosaurs created an odd reptilian-whale hybrid. This has yet another key lesson to learn here.

`

Now the continuation...

`

So after two months of playing with my Squalodon, I ended up with this the "Dolphinsauriod"...

So after two months of playing with my Squalodon, I ended up with this the "Dolphinsauriod"...

`

At the time, I just viewed this particular incarnation of the model as just another mistake.

At the time, I just viewed this particular incarnation of the model as just another mistake.

Looking at it now, the Dolphinsauriod marked the end of an era in my art. This was my last truly amateur approaches to reconstructions. As of April 2009 onward I would use one sort of reference or another when recreating anything, and thus have some degree of credibility in it.

However when starting the project in early 2009 I did not have many references for Squalodons. Even now having done extensive research on the family I've only managed to come up with a dozen or so. Of those only a few are worth looking at.

`

Bringing me to the first lesson of today's post...

`

Rule #3 of Scientific Restorations: There is no such thing as "enough" references. Track down as many pictures, drawings, photos, and restorations of a prehistoric subject's skeleton, body, and fossils. There is always another aspect or idea to be found in a new reference (even if it is just not to do it like a different recreation), so get as many as you possibly can!

`

This can be hard with less popular and obscure critters, like say Shark-Toothed Dolphins. So I'll take you through the useful references I managed to track down, and why I thought they were worth looking at.

There were several overly simplistic restorations, and of these I found this cover page by Alton Dooley for his description of Squalodon whitmorei to be any good.

Though the prey dolphins in this particular piece are a little too minimalist to reference, the Squalodon chomping down on them is surprisingly accurate. The overall proportions of the skull, fins, and body are all perfect. Making this useful for scaling my model.

If for nothing else, this picture also gave me some confidence. If this was among the top 50% of Squalodons out there, then I had a good shot at creating a new addition to this elite group of artwork.

Perhaps the most influential of all Squalodon recreations was this one by Geoffrey Cox. This comes from his amazing little popular science book Prehistoric Animals of New Zealand. (Though sadly out of print, this book is by far one of the best ever released on New Zealand fossils, and definitely has the best palaeo-art to accompany it. So if you are interested in the subject try to track down a copy).

Perhaps the most influential of all Squalodon recreations was this one by Geoffrey Cox. This comes from his amazing little popular science book Prehistoric Animals of New Zealand. (Though sadly out of print, this book is by far one of the best ever released on New Zealand fossils, and definitely has the best palaeo-art to accompany it. So if you are interested in the subject try to track down a copy).

I consider this the "type specimen" artwork of Squalodon from which most other palaeo-art restorations are based. Often in palaeo-art I find that someone will do one key version of an animal, and then 90% of later artists approaching the same subject tend to copy or borrow heavily from this first "type specimen". I'm planning on doing a post on this phenomenon later, but that is the general idea.

One of the most clear examples of this derivative referencing (which is not necessarily a bad thing, I point out, but it is just important to acknowledge) is Arthur Weasley's Squalodon from wikipedia. It is a nice piece, but where it is accurate it incorporates all of Cox's features.

Weasley's body and fin proportions are not very well measured, and so I didn't really use this picutre at all. It is worth crediting this piece with a pretty accurate skull though. At the same time I didn't use it as it rehashs all of Cox's ideas. It has the same skinny long slender snout, and the relatively spherical melon organ (what makes a whales forehead) as Cox's.

My favourite of the "Cox"ian Squalodons is Rob van Assan's version here. Again we see the same general head configuration with the long beak and very small round melon organ.

Not that I'm saying one has to reinvent the wheel with palaeo-art, especially if a pioneer artist captures something scientifically critical to an animal in their earlier version. However Squalodons' heads did not necessarily look like this. Dr. Fordyce has directed me to create a completely novel vision of Squalodon compared to the Cox idea (wait for this in Part 4).

Highlighting the fact that the look of Squalodons is not completely agreed upon, you'll notice Mr. Assan has put his own spin on the Dolphin. Instead of a dorsal fin he has added a river dolphin (the closest living relatives of Squalodons) ridge along the back. This gave some food for thought, and prompted Dr. Fordyce's opinion on the fin (again coming in Part 4).

A radical departure from the Cox model, is this rather Bottlenose Dolphin looking Squalodon by the Aquaheart Museum (as the majority of this site is in Japanese which I don't read, I couldn't find an artist's name. If you know the artist who created this piece of art please let us know in the comment section or email us at artevolved@blogspot.com.)

Though pretty much everything about this piece runs against what we know of the Shark Toothed Dolphins (in particular the lack of said shark-like teeth) as it is trying to mimic a modern Dolphin, the extant looking melon organ turns out to make this one of the key Squalodons I came across.

The best two sets of references I found combined aspects of both styles. The one set of pieces by Chris Gaskin I was asked not to post, as they are the property of Otago University. Chris Gaskin created the pieces for Dr. Fordyce in the 1990's, and so I found them a good guide to what the good doctor would want in his renditions (though as I'd find out, Dr. Fordyce's views on Squalodons have changed in the last 15 years).

The other pictures, such as the Waipatia above (a relative of Squalodons), came from a book accompanying a fossil whale exhibit from Japan. Sadly I only had access to Dr. Fordyce's copy, and the majority of the writing was in Japanese, so I was unable to get the artists name. If you know the artist who created this piece of art please let us know in the comment section or email us at artevolved@blogspot.com.

In both sets of pieces the long unusual snout of Squalodon and its enormous teeth are mixed with a much more modern Dolphin face (unlike the basketball Cox look).

Of course had I not been working with Dr. Fordyce my decisions as what to take from these different interpretations would have been difficult. It illustrates the common problem with palaeo-restorations already covered here at ART Evolved. When looking at references with no proper scientific input, it can be tricky.

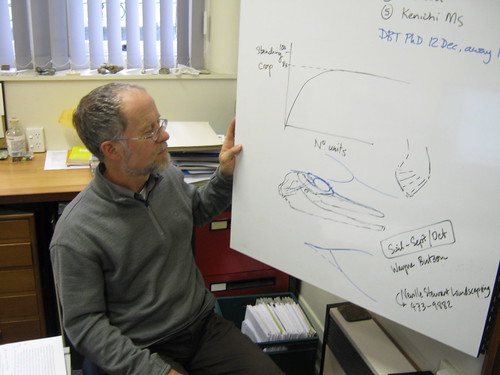

The most trust worth reference you are ever going to get is the fossil material itself. In my case this was just the skull. Only a few complete Squalodon skeletons have ever been collected, and none were from NZ or easy to access from here.

With each new approach I've taken on the whale since the first (in Part 1 of Flukes) I have ended up referring to the skull more and more. By my last rendition of the Squalodon (coming up in Part 4) the skull was my centre referral point. Which would be my other key piece of advice...

Rule #4 of Scientific Restorations: No matter how other references you find and how much you like other artists takes on a subject, always make sure the original fossils are your main guide. This way you can separate the "facts" in your other references from the "artistic licence and/or style" flavouring the artists may have injected into their piece.

So coming back to my art. This was the

Dolphinsauriod. Despite its reptilian flavour, many of the key

Squalodon features were starting to take form. I had the long snout, I had the large teeth (though at this stage they were a little too

exaggerated), I had something of a melon organ (though not correct in Dr.

Fordyce's opinion).

A rough comparison between the

Dolphinsauriod and the skull showed that my snout was not quite long enough, and a new factor not mentioned on the other restorations before (as they all got it correct) was the eye was far too high on the face.

The other key issue, causing my whale to look more like a marine reptile, was how I was lacking a proper Dolphin cheek.

After referencing the Japanese artwork and

Gaskin, plus some modern Dolphins, this is the fix I came up with.

Though it is quite rough in these early pics, already my Squalodon was looking a lot more mammalian. It was these finer tune details that I would learn much more about in the coming months and attempts.

Though it is quite rough in these early pics, already my Squalodon was looking a lot more mammalian. It was these finer tune details that I would learn much more about in the coming months and attempts.

For the time being (at the time) putting the teeth back into the skull made difference between mammal version 1 and Dolphinsauriod quite remarkable, despite the lack of polish on version 1.

For the time being (at the time) putting the teeth back into the skull made difference between mammal version 1 and Dolphinsauriod quite remarkable, despite the lack of polish on version 1.

Using my very crude model to fossil comparison, the new model was looking good. This technique however was very crude, and i was going to find out that I needed a lot more fine tune work. You can check out a preview of my new method of art to fossil comparisons here.

Using my very crude model to fossil comparison, the new model was looking good. This technique however was very crude, and i was going to find out that I needed a lot more fine tune work. You can check out a preview of my new method of art to fossil comparisons here.

Finally I was onto the base of the good copy...

Finally I was onto the base of the good copy...

Of course that still wasn't quite the same as having the good copy...

Of course that still wasn't quite the same as having the good copy...

More on that in Part 4!

Craig brings you the next chapter of his...

Craig brings you the next chapter of his...

So I'd managed to get my Squalodon looking something like a Dolphin should. Showing it to Dr. Fordyce I got my first passing grade on the restoration! It got a C- so to speak. All the details were wrong, but I'd gotten the general layout right. Which was a first!

So I'd managed to get my Squalodon looking something like a Dolphin should. Showing it to Dr. Fordyce I got my first passing grade on the restoration! It got a C- so to speak. All the details were wrong, but I'd gotten the general layout right. Which was a first! This is the format I came up with. A schematic of my Shark Toothed Dolphin from ever basic view available.

This is the format I came up with. A schematic of my Shark Toothed Dolphin from ever basic view available.

By this point in late 2009 I had been making some big breakthroughs across the board in my 3Ding (in large part thanks to ART Evolved). I now had a better method of creating underwater effects, which I promptly plopped my Squalodon into.

By this point in late 2009 I had been making some big breakthroughs across the board in my 3Ding (in large part thanks to ART Evolved). I now had a better method of creating underwater effects, which I promptly plopped my Squalodon into. By now I also had a firm grasp on 3D rigging, so the Shark Toothed Dolphin became my first model to be rigged by a single skeleton! (I typically rig each part separately, and simply pose them relative to each other).

By now I also had a firm grasp on 3D rigging, so the Shark Toothed Dolphin became my first model to be rigged by a single skeleton! (I typically rig each part separately, and simply pose them relative to each other).

Apart from the neck wrinkles and removing some of the model induced lines from the skull area, this Squalodon met with Dr. Fordyce's standards!

Apart from the neck wrinkles and removing some of the model induced lines from the skull area, this Squalodon met with Dr. Fordyce's standards! It was now time to develop a scene for this critter to steal!

It was now time to develop a scene for this critter to steal!

I personally run into problems with

I personally run into problems with  Further more if your reconstruction is in an unconventional pose, such as

Further more if your reconstruction is in an unconventional pose, such as

So after two months of playing with my

So after two months of playing with my  At the time, I just viewed this particular incarnation of the model as just another mistake.

At the time, I just viewed this particular incarnation of the model as just another mistake.

Perhaps the most

Perhaps the most

So coming back to my art. This was the

So coming back to my art. This was the  A rough comparison between the

A rough comparison between the  After referencing the Japanese artwork and

After referencing the Japanese artwork and  Though it is quite rough in these early pics, already my

Though it is quite rough in these early pics, already my  For the time being (at the time) putting the teeth back into the skull made difference between mammal version 1 and

For the time being (at the time) putting the teeth back into the skull made difference between mammal version 1 and  Using my very crude model to fossil comparison, the new model was looking good. This technique however was very crude, and i was going to find out that I needed a lot more fine

Using my very crude model to fossil comparison, the new model was looking good. This technique however was very crude, and i was going to find out that I needed a lot more fine  Finally I was onto the base of the good copy...

Finally I was onto the base of the good copy... I owe it all to this piece by

I owe it all to this piece by  Of course a concept is easy to picture in ones head. Getting it out of the mind and into the material world for others to see, that is the trick.

Of course a concept is easy to picture in ones head. Getting it out of the mind and into the material world for others to see, that is the trick. This is the answer I came up with to this challenge.

This is the answer I came up with to this challenge.

As I was aiming for my

As I was aiming for my  So here is a rough flow chart of my

So here is a rough flow chart of my  So the Monitor lizards were too tall (with my

So the Monitor lizards were too tall (with my

Along the way I of course did several double checks to ensure my

Along the way I of course did several double checks to ensure my  All things considered, I think I did a pretty good job. Not perfect mind you, but that is partially lighting (this

All things considered, I think I did a pretty good job. Not perfect mind you, but that is partially lighting (this