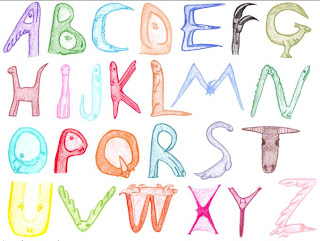

Prehistoric Animal Alphabet

Prehistoric Animal AlphabetColour pencil illustrations

June 2010

Above is a collection of twenty-six illustrations, each a stylised letter of the alphabet. They are styled to look like various prehistoric creatures, some are based loosely on existing types, others completely made up. All of them have been given a binomial, with each name beginning with the letter the animal represents, and a bit of geological/biological 'information' has been made up to go with each animal. To reiterate, none of these animals actually exists or have ever existed, and I cannot guarantee that all the names I have given them are unique and not synonyms (technically these are all

nomina nuda, but anyway, enjoy...)

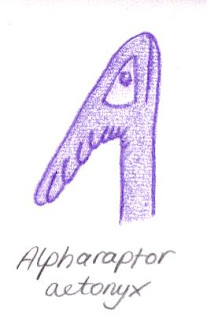

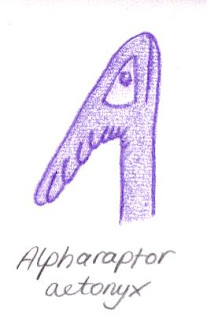

Alpharaptor aetonyx

Alpharaptor aetonyx (meaning 'eagle-clawed "A" plunderer) was a purple-feathered theropod from late Cretaceous China. It had large, eagle-like talons on all four limbs and preyed upon small birds and mammals.

Betasaurus beryllinus

Betasaurus beryllinus ('beryl-like "B" lizard) was a medium-sized hadrosaur from late Cretaceous Alberta. It lived in large herds to defend itself from large tyrannosaurs, and fed upon cycads. The B-shaped head enabled

Betasaurus to produce a sound somewhat like a euphonium.

Cyanosuchus cadaverinus

Cyanosuchus cadaverinus ('corpse-like blue crocodile', from the colour and odour of the fossil remains) was a mesoeucrocodylian from Early Cretaceous southern England. It was a fish-eater and swam in freshwater lagoons.

Deltaceratops dipsomanius

Deltaceratops dipsomanius ('alcoholic "D" horned face') was a protoceratopsid from Late Cretaceous Mongolia. It lived in deserts and fed upon whatever ground cover it could find. Its specific epithet '

dipsomanius' was derived from the sprawled position of the type specimen.

Epsilonodactylus erebennus

Epsilonodactylus erebennus ('gloomy "E" finger) was a pteranodontid pterosaur from Late Cretaceous Argentina. It was discovered on a particularly gloomy day. It was a fish-eater, being most partial to sharks. It is thus believed to be an oceanic wanderer, like today's albatrosses.

Falcunguis ferox

Falcunguis ferox ('ferocious sickle claw') is only known from the claws and phalanges of two digits. It is believed to be an ancestor of the therizinosaurs, due to its geological and geographical distribution in Early Cretaceous China.

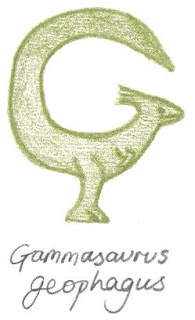

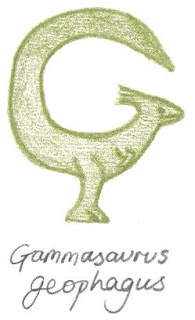

Gammasaurus geophagus

Gammasaurus geophagus ('earth eating "G" lizard) was a small coelurosaur with a very long tail which curved backwards over its body. It used the elongated tail to carry leaves which it used to shade itself in hot weather. It dates from the late Jurassic of Bavaria and ate large subterranean insects. Fossilised beetle remains were found in the stomachs of several well-preserved specimens of

Gammasaurus geophagus, but these were erroneously believed to be examples of fossilised earth (so basically, rocks).

Hypsiloura helioscopus

Hypsiloura helioscopus ('sky gazing high tail') was a camarasaurid from late Jurassic Montana. It was a medium-sized sauropod, capable of reaching tall monkey puzzles in search of foliage and pine cones. It was able to camouflage itself against the trunks of such trees by erecting its neck and tail and pretending to be a tree.

Iotatitan ischyrus

Iotatitan ischyrus ('strong "I" giant) was a titanosaurid from late Cretaceous Argentina. It was the largest sauropod ever known, and it is only known from a single partial cervical vertebra, but its total length has been extrapolated as anywhere from 27 m at the most conservative to 1.3 km at the other extreme. Since nothing is known of the skull or dentition, we cannot say anything about the diet of

Iotatitan, except that it definitely ate something, and a lot of it.

Jovigyrinus jocosus

Jovigyrinus jocosus ('joking Bon Jovi's salamander') was an early tetrapod from Devonian New Jersey. It was named after local rock band Bon Jovi. Jon Bon Jovi, the lead singer of the band, who is also an unsuccessful actor, has been quoted as saying about the animal, "Wow, at last something in the last two decades I can be proud of!" The animal was probably a predator of small fish and aquatic invertebrates such as trilobites in shallow seas, and would have had external gills like modern salamander larvae and axolotls.

Kappatherodon keiolophus

Kappatherodon keiolophus ('cloven-crested "K" mammal-tooth') was a sphenacodontid therapsid related to

Dimetrodon, but can be distinguished from it by its cloven back sail. Like its relative, it dates from the Permian of Texas and was a predator of smaller therapsids. It could only be active on hot days, between the hours of 10 and 11 a.m. and 1 and 2 p.m., unless it was during daylight savings time, when the hours are shifted an hour ahead. If

Kappatherodon overslept, it would starve and become food for many a hungry

Dimetrodon.

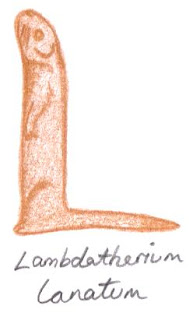

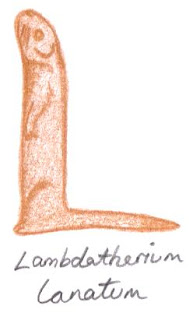

Lambdatherium lanatum

Lambdatherium lanatum ('woolly "L" mammal') was a multituberculate mammal from the Late Cretaceous of Kazakhstan. It was a colonial animal, living in mass burrow systems like rabbits or prairie dogs. It managed to survive beyond the K-T boundary, with remains of

Lambdatherium lanatum being found 10 million years into the Palaeocene, proving beyond doubt that dinosaurs were abducted by aliens.

Micromacropteryx minutissimus

Micromacropteryx minutissimus ('very tiny little thing with long wings') was the late Triassic equivalent of a hummingbird. Although there were no flowering plants at the time, individuals could be seen flitting from plant to plant looking for sources of nectar. Of course, because there was no such thing as nectar,

Micromacropteryx became hypercarnivorous, eating just about any flesh it could wrap its tiny jaws around.

Neonothosaurus natans

Neonothosaurus natans ('swimming new bastard lizard', for its unknown parentage, and the fact that it's not very nice) was not a true nothosaur, and was not even a reptile. It represents the only known member of a lineage of lissamphibians to have developed a coat of scales which makes it able to spend extended periods of time outside of water. It lived in early Triassic lakes across northern Pangaea, which was to become the supercontinent of Laurasia.

Omegaraptor ookleptes

Omegaraptor ookleptes ('egg-stealing "O" plunderer') was a large turquoise-coloured oviraptoran closely related to

Citipati osmolskae. Like that dinosaur,

Omegaraptor had a large and brightly-coloured head, and probably didn't steal eggs. That didn't stop one taxonomist from naming the species

ookleptes, because he felt that just because it hasn't been proven, doesn't mean it isn't true.

Piceratops psittacoides

Piceratops psittacoides ('parrot-like "P" horned face') is a close relative of

Psittacosaurus but is much larger. Reaching a maximum of 20 m,

Piceratops was easily the largest of the ceratopsians, and dwelled in Late Cretaceous forests in China.

Quinquecornis quintilis

Quinquecornis quintilis ('five horns of July') was the smallest of the ceratopsians, with adults reaching no more than 40 cm in length. Most of that length was taken up by the huge frill. As its name suggests, it has five horns: two small jugal horns on each side of the face; and a single large nasal horn. It lived in late Cretaceous North America. Fossils of

Q. quintilis are most often discovered in the month of July.

Rhosaurus reductus

Rhosaurus reductus ('aloof "R" lizard) was a prosauropod from Late Triassic South Africa. Just like the same region nowadays, South Africa was full of noisy buzzing sounds, but instead of coming from plastic vuvuzelas,

Rhosaurus would have contributed to the din. It was a plant eater but was believed to be nocturnal due to its large orbits, but this is now known to be where the buzzing sounds arise from. The nocturnal nature led early palaeontologists to believe

Rhosaurus was timid and aloof, hence the specific name.

Sigmacorypha suchophaga

Sigmacorypha suchophaga ('crocodile-eating "S" neck') was an elasmosaur, a group of long-necked plesiosaurs. It was a significant predator of

Cyanosuchus, eating several individuals in one sitting.

Tautherium tragocerum

Tautherium tragocerum ('goat-horned "T" mammal') was an ox-like ungulate from Miocene Tibet, occupying a similar niche to today's yak (

Bos grunniens). It had no external ears, because its ancestors were aquatic and had since lost their pinnae.

Upsilonobatrachus umbrivagus

Upsilonobatrachus umbrivagus ('shade-dwelling "U" frog') was a large temnospondyl amphibian from Carboniferous Spain. It would have preferred to lurk in the shade of tree ferns and other such plants whilst submerged in the water with its jaws agape, waiting for small fish to approach. Its yellow coloration is believed to be the earliest example of aposematic coloration known.

Virididipennis vorax

Virididipennis vorax ('with two green feathers and a huge appetite') was a small tree-dwelling reptile related to lizards and snakes but with large scaly outgrowths on the head which resemble feathers. The rest of the body is not known, but it has been suggested that it could be upto several miles long. It dwelled in Pliocene Thailand.

Woganosaurus williamsi

Woganosaurus williamsi ('Robin Williams's and Terry Wogan's lizard') was an early reptile that defies classification. It was found in Scotland in Carboniferous rocks by members of the BBC Radio 2 crew, and was named after the veteran host Terry Wogan. Robin Williams was honoured in the specific epithet due to the taxonomist's fondness for the movie

Mrs. Doubtfire.

Xipteryx xanthypothalassus

Xipteryx xanthypothalassus ('Yellow Submarine "X" wing') was an early primate which experimented with gliding. It had a pair of patagia between the ankle and wrist and would glide from tree to tree in Eocene Europe. The type specimen was discovered by Ringo Starr while touring. The species was named after one of his band's most popular songs, and one of the easiest to translate into Ancient Greek.

Yahoolophosaurus yptios

Yahoolophosaurus yptios ('upside-down Y.A.H.O.O. crested lizard') was a therapsid discovered in Permian Russia. It was found by members of the Young American Historical Ornithological Organisation who were on a field trip to Russia. The first specimen to be exhibited was mounted upside-down, hence the name, and why all reconstructions of the creature are upside-down.

Zetaornis zaocys

Zetaornis zaocys ('very fast "Z" bird') was a species of tern (family Sternidae) from Pliocene Alaska. It had disproportionally long wings to power its extremely fast flight. It has been suggested that it could have reached speeds of upto 186,000 miles per second, which is of course the speed of light.

Cross posted from my blog: The Disillusioned TaxonomistAll art and text by Mo Hassan